Canonising the Bard

Shakespeare and the Construction of National Culture in the Nineteenth Century

He was not of an age but for all time!

Ben Jonson (“To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare”)

The position William Shakespeare occupies in the English literary canon today—as the preeminent national poet and cultural touchstone—was not established in the centuries following his death. While his plays remained in circulation and were frequently performed throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was not until the nineteenth century that the idea of Shakespeare as England’s cultural icon was fully articulated and institutionally endorsed.

During the Romantic period, critics and writers such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, and Thomas De Quincey began to articulate a vision of Shakespeare that placed him beyond mere theatrical success or popular appeal. They presented him as a universal genius whose works expressed the deepest truths of human nature. This shift in tone from admiration to near-veneration laid the groundwork for the more structured cultural consecration that would follow in the Victorian period.

In Shakespeare one sentence begets the next naturally; the meaning is all inwoven. He goes on kindling like a meteor through the dark atmosphere; yet, when the creation in its outline is once perfect, then he seems to rest from his labour, and to smile upon his work, and tell himself that it is very good. You see many scenes and parts of scenes which are simply Shakespeare's, disporting himself in joyous triumph and vigorous fun after a great achievement of his highest genius.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (Table Talk, April 1833)

It was in the nineteenth century that Shakespeare was decisively canonised—not only as a literary figure, but as a symbol of national identity and moral authority. The Victorian era witnessed a proliferation of complete editions, often handsomely illustrated and marketed to middle-class households, which presented Shakespeare’s works as suitable for domestic reading and moral instruction. His plays became fixtures in educational curricula and were invoked in parliamentary debates, sermons, and public discourse as embodiments of English virtues and values.

This institutionalisation of Shakespeare’s status was deeply entangled with the broader cultural and political currents of the British Empire. As Britain expanded its global reach, there arose a corresponding desire to assert a coherent and elevated national culture, one that could stand alongside the grandeur of Roman and Greek antiquity. Shakespeare, with his linguistic mastery, thematic range, and capacious vision of humanity, served as an ideal representative for this project. He could be interpreted as both timeless and particularly English, as both universal and uniquely national.

Commemorative practices also played a crucial role in this cultural construction. Shakespeare’s birthday (April 23rd) became a symbolic occasion for national celebration. The preservation and promotion of Stratford-upon-Avon as a site of pilgrimage, the erection of statues and memorials across the empire, and the establishment of Shakespeare societies all contributed to the sense of a shared cultural inheritance. Reading, quoting, and revering Shakespeare became intertwined with ideals of education, civility, and belonging.

The 1769 Jubilee: Shakespeare as Celebrity

Before the full-scale cultural canonisation of Shakespeare in the nineteenth century, there was the curious and theatrical spectacle of the 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee, an event that reveals how the eighteenth century began to shape, but had not yet solidified, the bard’s cultural status.

Organised by the celebrated actor David Garrick and held in Stratford-upon-Avon, the Jubilee was conceived as a grand celebration of Shakespeare’s legacy. It was the first large-scale public event dedicated to the playwright and marked a significant step in transforming him from an admired dramatist into a figure of national importance. The three-day festival included processions, banquets, fireworks, concerts, and the recitation of Garrick’s specially written “Ode to Shakespeare”. Ironically, no actual performance of a Shakespeare play was scheduled (likely due to weather concerns—a heavy rain poured on the second day! and a lack of facilities) which highlights how Shakespeare’s symbolic importance had begun to eclipse the plays themselves.

The Jubilee was, in many ways, more theatrical than literary. It leaned into the language of spectacle and entertainment, and it was deeply tied to Garrick’s own celebrity and commercial interests. His image as the great interpreter of Shakespeare blurred with the image of Shakespeare himself, resulting in a kind of cultural pageantry that celebrated Shakespeare as a popular icon rather than a moral or national philosopher.

David Garrick, 1717 - 1779. Actor and dramatist, reciting the Ode in honour of Shakespeare at Stratford @ Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Despite being mocked by some contemporaries for its extravagance and its descent into farce (the heavy rain forced the cancellation of major outdoor events), the Jubilee planted the seeds for a more structured reverence. It popularised the idea of Stratford as a site of pilgrimage, and it demonstrated that Shakespeare could serve as a unifying cultural figure in an age increasingly preoccupied with national identity.

The Boydell Shakespeare (1791-1805)

One of the most ambitious cultural enterprises of the late eighteenth century, the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery (1791–1805) represents a crucial moment in the visual and national canonisation of Shakespeare. Conceived by publisher and entrepreneur John Boydell, the project aimed to establish a British school of history painting by commissioning prominent artists to create large-scale paintings based on scenes from Shakespeare's plays. These works were exhibited in a purpose-built gallery in Pall Mall, London, and later engraved and published alongside a lavish new edition of Shakespeare’s complete works. The Boydell Shakespeare thus brought together art, literature, and commerce in a patriotic celebration of England’s national poet.

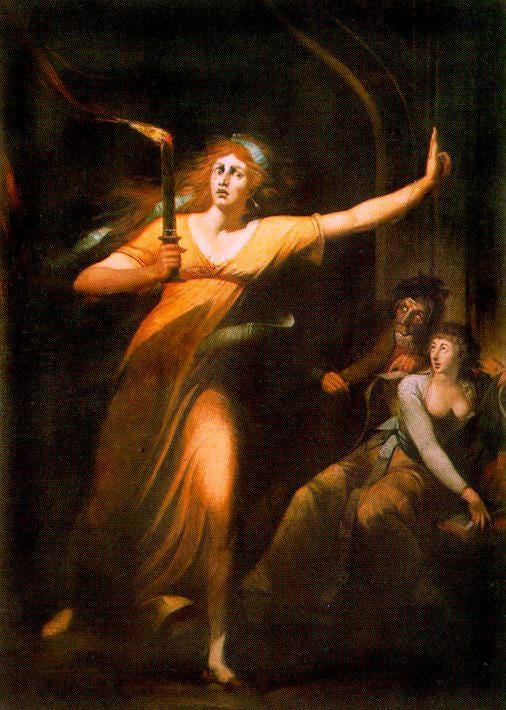

The gallery not only elevated Shakespeare to the status of high art but also made his work a vehicle for British cultural ambition. By investing in Shakespearean themes, Boydell aligned his enterprise with a growing sense of national identity and imperial pride. The project mobilised some of the era’s most celebrated artists—including Joshua Reynolds, Henry Fuseli [see painting below], and James Northcote—whose dramatic interpretations helped fix certain visual and emotional associations with Shakespeare’s characters and scenes. Though the gallery eventually succumbed to financial difficulties and the political upheaval of the Napoleonic Wars, it played a significant role in shaping the public image of Shakespeare in the Romantic and early Victorian imagination: as a figure not only of literary genius but of visual grandeur, cultural prestige, and national significance.

“The Sleepwalking Lady Macbeth” Henry Fuseli @ Paris, Musée du Louvre.

The transition from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century marks a decisive turning point in the cultural afterlife of Shakespeare. What had begun as a series of patriotic gestures (evident in David Garrick’s Stratford Jubilee and the Boydell Gallery) evolved into a more profound intellectual and aesthetic engagement with Shakespeare’s works. Romantic writers such as Coleridge, Keats, and Hazlitt no longer admired Shakespeare solely as a national treasure, but revered him as a universal genius: a poet-philosopher who embodied the complexity of human nature and the imaginative depth to which literature could aspire. By the early nineteenth century, Shakespeare had become more than England’s greatest dramatist; he was a moral and metaphysical touchstone, a figure through whom successive generations sought to articulate their highest artistic and cultural ideals.

This legacy endures, even as twenty-first-century scholarship continues to interrogate the political implications of his canonisation and the ideologies his works have been made to serve.

The genius of Shakespeare was an innate universality; wherefore he laid the achievements of human intellect prostrate beneath his indolent and kingly gaze.

John Keats (Life, letters, and literary remains, of John Keats)

Want to study literature with me? Check the available online courses and workshops at Books & Culture!

Across the centuries, Shakespeare’s words continue to ripple like a river undeterred by time — shaping shores of thought, feeling, and imagination. Yet even the strongest currents invite questioning: whose voices are lifted, whose dreams are left drifting beyond the canon’s reach? In honoring brilliance, we are also called to expand the sky, making room for stars yet unnamed.

How might we celebrate the timeless while also tending the fields where new voices are waiting to rise and sing? ∞