Why does Satan steal the spotlight in a poem meant to “justify the ways of God to men”?

I taught Paradise Lost to my students this week, and it really got me thinking.

That question is the paradox at the heart of John Milton’s monumental epic. Though its theological scaffolding is unmistakably Christian, it is Satan—not God, not Adam—who dominates the opening books of the poem with a voice that is magnetic, thunderous, and strangely heroic.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less than he

Whom thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; th’ Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence:

Here we may reign secure; and, in my choice,

To reign is worth ambition, though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.(Paradise Lost, Book I, ll. 254-263)

In this moment, Satan is talking to his fellow fallen angels in Hell, putting forward his ambition, and declaring that it is better to rule in the pits of Hell, suffering, than to be submissive to God in Heaven. It is a chilling declaration of autonomy over obedience. But the question is: does Milton admire Satan, or is he offering a cautionary tale of pride, rebellion, and self-delusion?

One of Gustave Doré’s illustrations of Paradise Lost

The Byronic Blueprint?

Centuries before Byron penned his moody protagonists, Milton gave us a figure whose rebellion springs from a powerful combination of ambition and injured pride. Satan’s war against Heaven fails, yet he emerges from the “fiery gulf” resolute, forging a kingdom in exile. His famous speeches stir a sense of tragic grandeur. Thus, is Satan a revolutionary hero, a Prometheus for the Christian imagination, or the embodiment of egotism and despair?

One of Satan’s great powers is language. He’s a master orator who can spin failure into martyrdom, cowardice into strategy. When he speaks to his fellow fallen angels or tempts Eve in the Garden, his words seduce as much as they deceive.

Satan’s rhetoric skills pose a challenge for readers: are we drawn to Satan because of who he is, or because of how he speaks?

Milton, who witnessed Charles I’s execution for treason, lived through the political upheavals of the English Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s government, knew a thing or two about the power of rhetoric and the dangers of persuasive tyrants. Satan may begin as a rebel, but he ends as a tyrant himself, ruling in Hell with fear, not freedom.

Satan and the Romantic Imagination

It was the Romantics who truly crowned Milton’s Satan with the laurels of a tragic hero.

While earlier readers often viewed Satan as a cautionary emblem of rebellion, the Romantic poets saw in him something far more compelling: the image of the isolated, tormented genius. For them, Satan became the prototype of the alienated individual, driven by passion, condemned by society, yet defiantly self-determining.

Another illustration by Gustave Doré

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake famously declared that Milton was “a true Poet, of the Devil’s party without knowing it,” suggesting that the poet’s imaginative energy surged most powerfully when writing Satan. Percy Bysshe Shelley, in A Defense of Poetry, wrote: “Nothing can exceed the energy and magnificence of the character of Satan as expressed in Paradise Lost. It is a mistake to suppose that he could ever have been intended for the popular personification of evil.” Shelley praises the fallen angel’s refusal to bow, even in defeat.

What the Romantics recognized and celebrated was the emotional intensity of Satan’s struggle: his grand speeches, his suffering, his refusal to submit. In an age that revered the individual will, the sublime, and the stormy depths of the soul, Milton’s Satan offered a mirror for their own artistic identity: passionate, misunderstood, and doomed to greatness.

But there’s a twist.

In Paradise Lost, Satan’s arc is not one of liberation but of decline. His soaring rhetoric gives way to bitterness. By the later books, he is reduced to a slinking serpent, envious of Adam and Eve’s innocence. The Romantics, then, read selectively, highlighting the grandeur of his rebellion while downplaying the moral and psychological unraveling that follows.

Still, their fascination left a mark. From Byron’s Lucifer in Cain to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, echoes of Milton’s Satan ripple across Romantic literature: figures who defy divine or social order in pursuit of knowledge, freedom, or simply the right to feel deeply. Satan became the Romantic spirit—fallen, fiery, unforgettable.

Visual Depictions of Satan in the Romantic Era

As poets like Blake, Shelley, and Byron reimagined Milton’s Satan as a figure of tragic grandeur, visual artists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries followed suit, translating his fall, fury, and isolation into arresting imagery.

These artists weren’t just illustrating Paradise Lost; they were giving visual form to a cultural fascination with rebellion, suffering, and sublime power. In their hands, Satan becomes more than a Biblical antagonist; he’s an emblem of heroic defiance, intellectual struggle, and spiritual exile.

Blake, poet and visual artist, didn’t just read Milton—he saw him. In his illustrated editions of Paradise Lost, Blake’s depictions of Satan are strikingly nuanced. Sometimes majestic, sometimes monstrous, Blake’s Satan often appears deeply human: muscular but melancholy, radiant yet tormented. One of his most famous images, Satan Arousing the Rebel Angels (see below), shows a figure rising with tremendous force, surrounded by the chaos of battle.

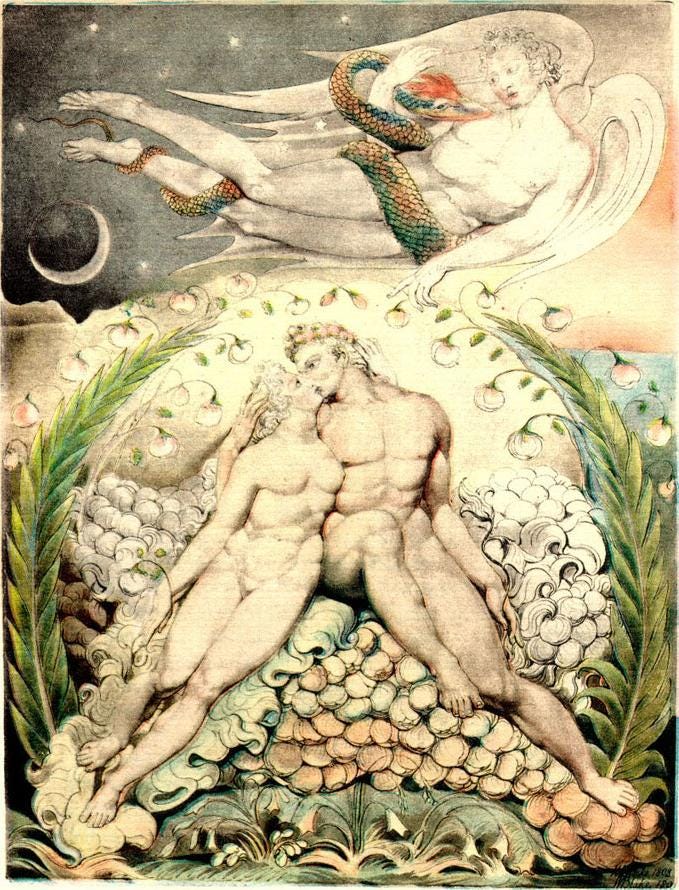

But Blake also captures Satan’s envy and inner ruin. In Satan Watching the Caresses of Adam and Eve, we see him flying above Adam and Eve, the serpent around his body, a voyeur, more pitiful than terrifying:

Some critics have pointed out that Eve is actually looking at Satan instead of Adam. What do you think?

No visual interpretation of Paradise Lost has been more enduring (or more influential) than the engravings of Gustave Doré (1832–1883), published in 1866.

Drawing from both classical statuary and Romantic melancholy, Doré renders Satan not as a grotesque demon but as a godlike figure cast down. Towering wings, chiseled form, and anguished expressions characterise many of his scenes, capturing the full emotional spectrum of Satan’s fall: wrath, despair, pride, and regret.

This is one of my favourite of Doré’s illustrations, of Satan overlooking Paradise (God’s creation he wishes to destroy):

Doré’s mastery of chiaroscuro imbues his illustrations with a sense of the epic and the eternal. In the above picture, he is a dark silhouette against a glowing orb of creation, isolated and estranged. It is impossible not to contrast it with Caspar David Friedrich’s ultimate Romantic painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

Doré’s contrasts heighten Satan’s tragedy: he is rarely shown in the act of evil, but rather in moments of introspection, exile, or ruin. Doré captures not just the fall from heaven, but the psychological weight of having once stood there.

In the end, Milton’s Satan endures because he refuses to be easily defined. He is at once villain and antihero, tyrant and rebel, sublime and damned. Romantic poets saw in him the prototype of the modern self—alienated, ambitious, and perpetually at war with both heaven and hell. Visual artists rendered his fall not just as punishment, but as spectacle, as poetry, as tragedy. Satan remains a figure through whom generations have explored the darker reaches of imagination, freedom, and defiance. Paradise Lost may begin in Hell, but its Satan continues to haunt us: still falling, still speaking, still burning with “the unconquerable will.”

Currently reading “What in Me Is Dark.”

“What in Me Is Dark tells the unlikely story of how Milton’s epic poem came to haunt political struggles over the past four centuries, including the many different, unexpected, often contradictory ways in which it has been read, interpreted, and appropriated through time and across the world, and to revolutionary ends.”

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/756556/what-in-me-is-dark-by-orlando-reade/

I love 'Paradise Lost'. Satan is the focus because who else is such an interesting character? As an atheist I am able to read without unnecessary bias of religious conditioning. In his blindness Milton sees evil as it is, oddly seductive, but fatally flawed.