In the carefully ordered worlds of Jane Austen’s novels, where social decorum and economic concerns dominate, acts of reading often carry a subversive charge. Austen’s heroines, more than merely well-read, are shaped by their engagement with literature. Their reading habits reflect intellect, sensibility, and moral independence. These traits distinguish them within a society that often attempts to constrain women’s thought and agency.

Austen’s interest in the act of reading is both thematic and metafictional. Northanger Abbey, her most overtly literary novel (and one of my favourites!), positions its young protagonist Catherine Morland as a naïve yet earnest consumer of Gothic fiction. Her misinterpretations of social reality, filtered through the melodramatic lens of Radcliffean narratives, satirize both genre conventions and the limitations placed on women’s education. Yet Austen’s critique is not directed at Catherine’s reading per se; rather, she exposes the hypocrisy of a society that ridicules young women for reading “silly novels” while denying them access to more rigorous intellectual training. In defending the novel form and its readers, Austen subtly elevates reading as a practice of discernment and personal growth.

This is one of my favourite extracts of the novel, in which the narrator advocates for the significance of the novel, in Austen’s witty sarcastic way:

“From pride, ignorance, or fashion, our foes are almost as many as our readers. And while the abilities of the nine-hundredth abridger of the History of England, or of the man who collects and publishes in a volume some dozen lines of Milton, Pope, and Prior, with a paper from the Spectator, and a chapter from Sterne, are eulogized by a thousand pens—there seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labour of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them. “I am no novel-reader—I seldom look into novels—Do not imagine that I often read novels—It is really very well for a novel.” Such is the common cant. “And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

(Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen)

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet’s relationship to books signals a more mature engagement with reading. Her wit and judgment are consistently aligned with her literacy; not only her ability to read texts, but to “read” character, motivation, and social nuance. Her preference for reading over dancing at the Meryton assembly early in the novel immediately establishes her independence of thought. Moreover, the development of her relationship with Mr. Darcy hinges on mutual intellectual respect. Reading becomes a framework for self-reflection and emotional maturation, both necessary for the novel’s eventual romantic resolution.

Persuasion offers perhaps the most poignant example of Austen’s investment in reading as consolation and interiority. Anne Elliot, isolated in a vain and superficial family, turns to literature as a source of emotional and moral sustenance. Her engagement with poetry, particularly her interactions with the grieving Captain Benwick, demonstrates her ability to interpret and respond to literature with depth and empathy. In contrast to Benwick’s performative melancholy, Anne’s thoughtful readings reveal an ethical intelligence rooted in lived experience.

The Commonplace book: Reading as creative art

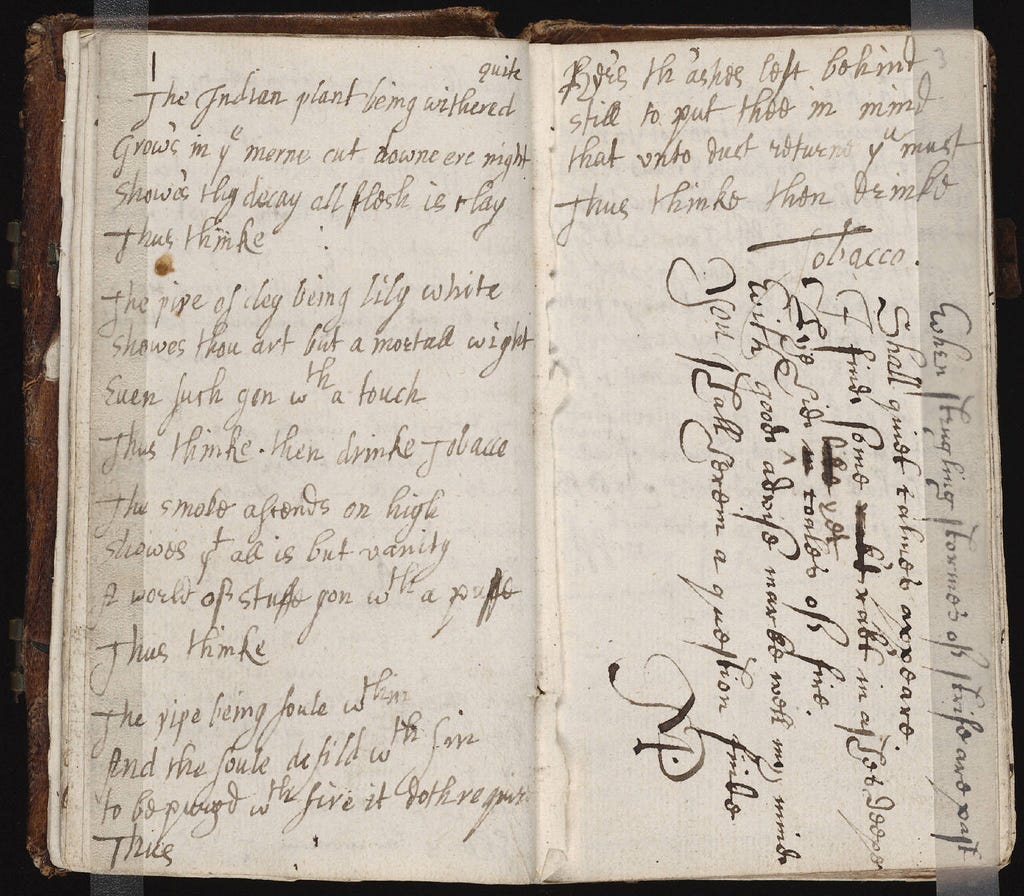

One important yet often overlooked aspect of historical reading culture is the keeping of a commonplace book. In my opinion, it is such a fascinating topic! These were private collections of quotations, reflections, literary excerpts, and even copied poems or moral observations, often handwritten into bound volumes. It was a place where one could create a personal archive. For women, whose access to formal education was limited and whose intellectual pursuits were often confined to the domestic sphere, the commonplace book served as a space of intellectual autonomy.

A 17th-century commonplace book. James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Bibliographic Record Number: 2031683 Call Number: Osborn b205

Though Austen never explicitly describes her heroines keeping commonplace books, many of them seem to read in a way that reflects this tradition: attentive, selective, and meditative. The commonplace book was also a kind of proto-social media: a curated self, assembled through excerpts and ideas drawn from a wide reading life. It was part literary scrapbook, part philosophical diary. In Austen’s time, to keep such a book was to claim one’s place in the literary conversation, even if that conversation remained private. It reflected not only what one read, but how one thought.

In modern terms, we might think of the commonplace book as a precursor to the scrapbook, the annotated margins, the underlined passage, the quote saved on a phone, or the literary journal tucked beside the bed. It reminds us that reading is not passive; it is generative. This type of meaningful active reading is what I call creative reading, and what I practice at Books & Culture.

Jane Austen, the Reader

Austen was, by all accounts, a voracious and discerning reader. Her letters reveal a lively engagement with contemporary fiction, history, moral philosophy, and even the occasional sermon. Far from reading purely for amusement, Austen read critically and with a writer’s eye, attuned to style, structure, and the subtleties of character portrayal.

The Austen family library was substantial by middle-class standards of the time, and Jane had access not only to books at home but also to circulating libraries, a key feature of Regency reading culture. These libraries made books, especially novels, more accessible to a growing literate public, and they offered women in particular a gateway into the intellectual and imaginative life of the period. Austen’s fiction often gestures to this world: characters borrow novels from friends or libraries, they discuss reading habits, they quote or misquote favorite authors.

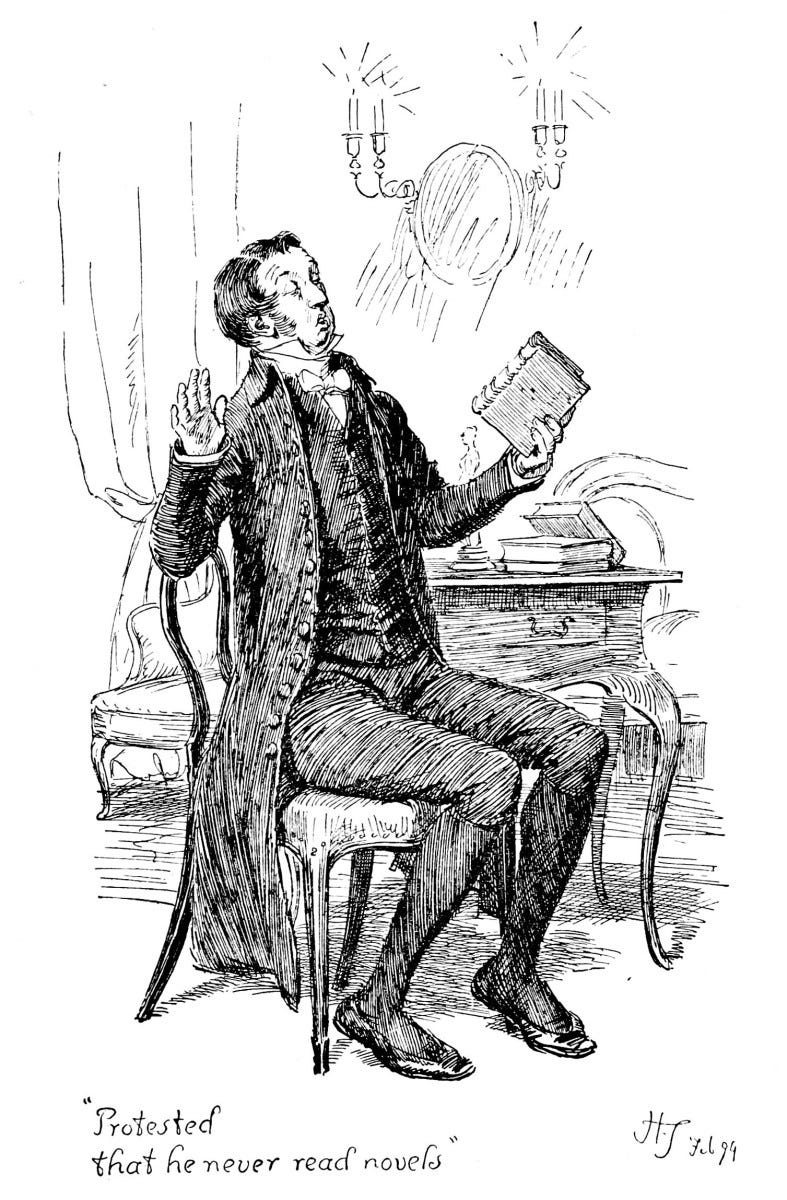

A funny passage from Pride and Prejudice comes from Chapter XIV, when the tedious Mr. Collins—Mr. Bennet’s heir, since he had no male children—chooses an excerpt to read aloud to the Bennet girls:

By tea-time, however, the dose had been enough, and Mr. Bennet was glad to take his guest into the drawing-room again, and when tea was over, glad to invite him to read aloud to the ladies. Mr. Collins readily assented, and a book was produced; but on beholding it (for everything announced it to be from a circulating library) he started back, and, begging pardon, protested that he never read novels. Kitty stared at him, and Lydia exclaimed. Other books were produced, and after some deliberation he chose “Fordyce’s Sermons.” Lydia gaped as he opened the volume; and before he had, with very monotonous solemnity, read three pages, she interrupted him with,—

“Do you know, mamma, that my uncle Philips talks of turning away Richard? and if he does, Colonel Forster will hire him. My aunt told me so herself on Saturday. I shall walk to Meryton to-morrow to hear more about it, and to ask when Mr. Denny comes back from town.”

Lydia was bid by her two eldest sisters to hold her tongue; but Mr. Collins, much offended, laid aside his book, and said,—

“I have often observed how little young ladies are interested by books of a serious stamp, though written solely for their benefit. It amazes me, I confess; for certainly there can be nothing so advantageous to them as instruction. But I will no longer importune my young cousin.”

(Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen)

This moment functions as a comic but pointed critique of patriarchal moral instruction. Austen uses Mr. Collins’s pompous delivery and Lydia’s impatience to expose the gap between prescriptive conduct literature and the real intellectual and emotional lives of women. Far from endorsing the didacticism of Fordyce’s Sermons, Austen mocks its moralizing tone and questions the assumption that young women should be passive recipients of male advice.

We also know that Austen read aloud regularly, both her own works-in-progress and those of others. Reading aloud was a common family practice in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and in the Austen household, it became both an entertainment and a form of literary critique. This oral dimension of reading meant that novels were social as well as solitary experiences. Her sharp ear for dialogue and irony was no doubt shaped by this practice.

Importantly, Austen’s reading extended well beyond fiction. She was deeply familiar with Samuel Johnson’s essays, admired the poetry of Cowper, and followed contemporary political developments with interest—even though these were considered “un-feminine” topics.

In a time when female literacy was on the rise but often dismissed or trivialized, Austen asserts the novel and the woman reader as central to cultural and moral discourse. To read her novels attentively is to witness a quiet revolution: one in which books do not merely reflect the world but reshape it, one reader at a time.

Want to study Jane Austen’s novels with me? We dig deep into her novels, context of publication, private life, unfinished works, letters, critical reception, and more, in the online course “The Jane Austen Club” at Books & Culture. Click here to know more.

Which is precisely why they are banning books, stopping funding to NOR and PBS, trying to control curriculum in schools and universities.

. पुस्तकालय🐵

"એપ્રિલમાં એક તેજસ્વી ઠંડો દિવસ હતો, અને ઘડિયાળોમાં તેર વાગી રહ્યા હતા." (૧૯૪૯)

આ શરૂઆતના વાક્યના ભાગ - ફક્ત એક તેજસ્વી વસંત દિવસ - અને બીજા ભાગ - ડુક્કર ઉડવા જેવું - વચ્ચેનો દ્વિભાજન ઓરવેલની ડિસ્ટોપિયન નવલકથા માટે એક તેજસ્વી શરૂઆત બનાવે છે. સ્પષ્ટપણે, આ ભવિષ્યમાં બધું બરાબર નથી જ્યાં પાર્ટી બધું નિયંત્રિત કરે છે, અને એક સામાન્ય માણસ પાછળ ધકેલવાની હિંમત કરે છે