There’s a certain kind of woman who haunts the pages of Victorian novels. Neither mistress of the house nor servant, neither wholly respectable nor entirely disreputable, she stands in the threshold of two worlds, an ambiguous figure in a tightly ordered social hierarchy. She is the governess.

Victorian literature is full of governesses. They appear with quiet regularity, often tucked into the corners of grand households, teaching French and embroidery, reading poetry aloud in firelit parlors, instructing precocious children in drawing rooms too vast to warm with just a single fire. But if they seem peripheral at first glance, governesses are often central to the emotional and moral machinery of the novels in which they appear. And they are far from passive.

Take, for instance, the most famous governess of them all: Jane Eyre (one of my favourite novels!). Charlotte Brontë’s plain, principled heroine becomes a governess not out of ambition but necessity. She has no fortune, no family, no prospects, but she does have a fierce sense of self and a powerful moral compass. As a governess at Thornfield Hall, she finds herself both part of and separate from the household she serves. She sits with her employer, Mr. Rochester, and his guests, but never fully belongs. Her ambiguous status allows her a kind of freedom, but it also renders her profoundly vulnerable. In many ways, Jane Eyre is a story about how a woman without social power carves out a space to assert her voice, her agency, and her moral vision in a world that rarely listens to women like her.

Look at the following extract, taken from Chapter 23, a pivotal moment in the novel, where Jane takes control of her own life, making decisions on her own moral and spiritual principles:

Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!—I have as much soul as you,—and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh;—it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal,—as we are!

(Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë)

Jane’s outcry is not only a declaration of love; it is a refusal to be diminished by class, gender, or employment. As a governess, she occupies an in-between space in the household, but in this speech she transcends those limits, insisting on her fundamental equality. It’s a moment that reveals the radical potential of the governess in fiction: not a passive observer, but a woman with fierce conviction and a voice that demands to be heard.

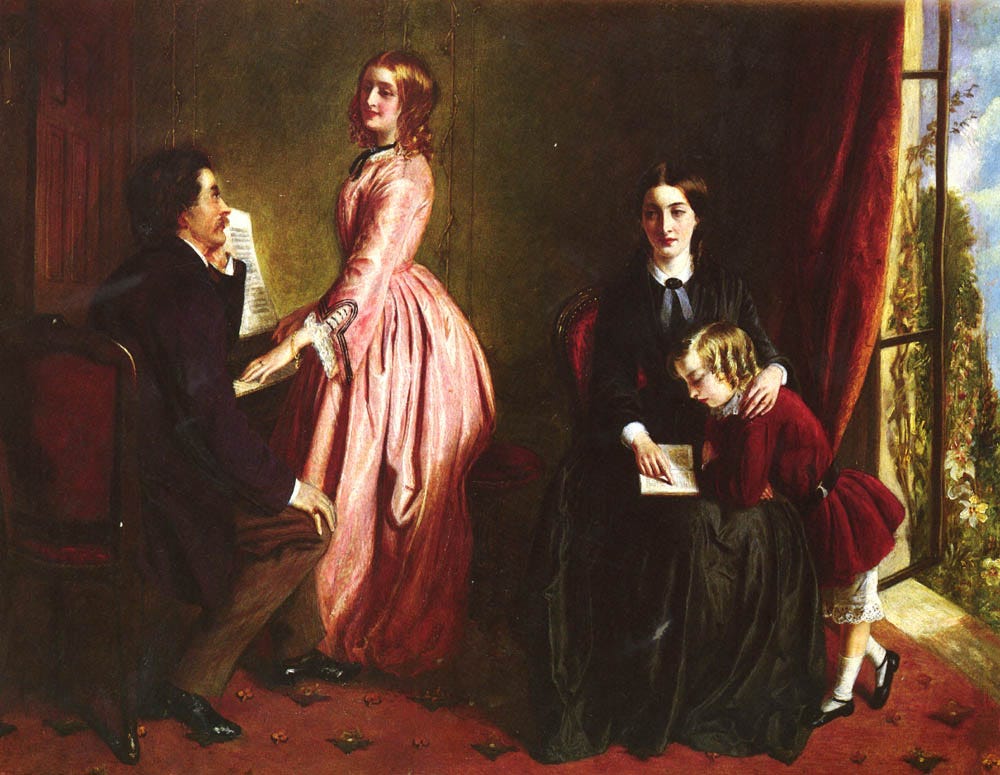

The Governess, Richard Redgrave (1804–1888). Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Another example is the nameless governess in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (another of my favourite novels!), one of the most enigmatic narrators in Victorian fiction. Hired to take care of two orphaned children at a remote country estate, she quickly becomes convinced that malevolent spirits are influencing her young charges. Whether she is a heroic protector or a dangerously repressed woman unraveling in isolation is a question that continues to divide readers. James’s governess is not simply a victim of supernatural forces, she may be the architect of her own haunting.

Even in less canonical novels, the governess appears as a figure of contradiction. In Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey, the heroine experiences the drudgery, humiliation, and loneliness of governessing firsthand. The job is isolating and often thankless; Agnes is expected to maintain control without authority, to educate without support, and to live within the household without truly belonging to it. Yet Anne Brontë also insists on the governess’s dignity, her intelligence, and her moral clarity.

The governess fascinated Victorian authors because she unsettled boundaries. She was educated, but not wealthy. She was respectable, but worked for a living. She had authority over children, but no power within the family. She could observe the domestic world with an insider’s access and an outsider’s eye. In other words, she was perfectly positioned to reveal the cracks in the façade of Victorian domesticity. Her story is one of economic precarity, emotional resilience, and moral resistance. It is also a story about voice: how to speak when you are expected to remain silent.

The Governess, Rebecca Solomon (1832-1886).

Governesses and the women who wrote them

It’s no accident that some of the most vivid portraits of governesses in Victorian literature were written by women who had lived that very life.

For many middle-class women in the nineteenth century, becoming a governess was one of the few socially acceptable ways to earn a living. It was also a deeply precarious role: emotionally isolating, economically unstable, and socially ambiguous. But for some, the governess’s room became the writer’s first study. The very experiences that confined and constrained them gave rise to the stories they would later tell.

Charlotte and Anne Brontë both worked as governesses before becoming published authors. Their novels Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey are not only works of fiction but thinly veiled reflections on their own encounters with wealthy families, unruly children, and the quiet humiliations of domestic employment. In their hands, the governess becomes a vehicle for exploring larger questions of female autonomy, class conflict, and emotional integrity.

The Brontë Sisters (Anne Brontë; Emily Brontë; Charlotte Brontë), by Patrick Branwell Brontë, oil on canvas, circa 1834, NPG 1725. ©National Portrait Gallery, London

Governess novels do more than bear witness, they protest! They illuminate the narrow corridors available to educated but impoverished women, and they expose the moral and emotional labor demanded of them. Brontë heroines often refuse to be diminished by their circumstances, asserting dignity and voice in places where women were expected to be invisible.

Writing about governesses also allowed women authors to reflect on their own experiences of marginality in the literary world. Much like the governess, the woman writer had to balance societal expectations with private ambition, professionalism with femininity, voice with restraint.

In the Books & Culture YouTube channel, we have read and discussed Anne Brontë’s novel Agnes Grey. You can watch the guided reading sessions here.

So interesting. This makes me want to read more Brontë books!! I think it’s also interesting to note what happens to the old governesses who are no longer needed to teach but rely on the family’s sense of duty to stay with them

on retirement. I’ve just read The Woman in White so thinking of Mrs Vesey , or in 20thC lit Miss Milliment in Elizabeth Jane Howard’s Cazalet Chronicles

I love Agnes Grey. More than Jane Eyre truth be told. The final scene always makes me teary.