This week, I have been teaching Hamlet to my third-year BA students. In preparation for the class discussion, we have read the chapter “The Art of Memory” in Hester Lees-Jeffries’ fascinating book Shakespeare & Memory.1 Shakespeare’s tragedy creates a dialogue with Early Modern practices of remembering from the very beginning. Who can forget the Ghost’s uncanny command to his son, “Remember me” (1.5.91)? With these lines, the murdered king is not merely asking for personal grief but invoking a rich tradition of memory practices that shaped how audiences in Shakespeare’s time understood history, identity, and justice.

The Art of Memory in Early Modern England

In the 16th and 17th centuries, memory was not just a passive recollection of the past; it was an active process. Educated individuals were trained in the ars memoriae, or the art of memory, a system that dates back to classical antiquity. This technique involved associating ideas with vivid mental images and spatial arrangements, a practice believed to strengthen recall and facilitate deep thinking.

Many of these techniques were inspired by the work of Cicero and Quintilian, who described how orators could “place” memories in imaginary architectures, such as a palace or a theatre, retrieving them when needed. Renaissance humanists and scholars, including Erasmus and Peter Ramus, adapted these methods for their own purposes, linking memory to moral reflection and self-governance.

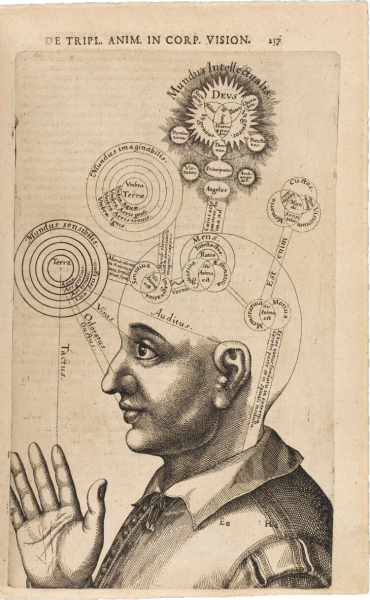

Such memory places would help the student to store information, and to easily retrieve it when needed. This memory technique has to do with how Early Modern thinkers understood the mind; they believed it consisted of three faculties: imagination (or fancy), reason, and memory. This tripartite model was influenced by classical and medieval theories of cognition, which suggested that each faculty had a distinct role in processing knowledge.

Imagination (or Fancy): The faculty responsible for generating images, emotions, and creative thought. It was often seen as the most unstable and deceptive part of the mind, capable of producing illusions and leading individuals into error.

Reason: The rational and logical faculty that governed judgment and decision-making. It was thought to balance and regulate the other faculties, ensuring clear thinking and moral action.

Memory: The storehouse of past experiences, lessons, and inherited wisdom. It was closely linked to identity and truth, as it preserved knowledge and shaped one’s understanding of history.

According to Lees-Jeffries,

“Fancy occupied the front of the brain, because it was closely associated with the eyes; […] Reason, the ‘highest’ part of the mind, was in the middle, and memory was located at the back of the head.” (p.13)

Ars Memoriæ, by Robert Fludd

Hamlet’s memory place

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is deeply infused with this mnemonic culture. The young prince explicitly speaks in terms of memory’s architecture, promising to erase all trivial recollections from “the table of my memory”, as if his mind were a wax tablet to be wiped clean and rewritten:

Remember thee?

Ay, thou poor ghost, whiles memory holds a seat

In this distracted globe. Remember thee?

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial, fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there,

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain,

Unmixed with baser matter. Yes, by heaven!

O most pernicious woman!

O villain, villain, smiling, damnèd villain!

My tables—meet it is I set it down

That one may smile and smile and be a villain.

At least I am sure it may be so in Denmark.

⌜He writes.⌝

So, uncle, there you are. Now to my word.

It is “adieu, adieu, remember me.”

I have sworn ’t.

(1.5.95-112)

Writing on wax tablets was a common practice in the Early Modern period. As Lees-Jeffries explains,

“paper was relatively expensive, especially blank paper, and this is partly why the blank leaves of early modern printed books are so often filled with notes unrelated to their contents. For the sorts of notes that someone might make ‘on the go’, as an intermediate stage on the way to another medium (the commonplace book, for example), it was far more convenient to be able to write on something portable and reusable.” (p. 22-23)

Wax tablets, which had been used since antiquity, consisted of wooden frames filled with a layer of wax, onto which notes and reminders could be inscribed using a stylus. The wax surface could be smoothed over and rewritten, making these tablets a flexible tool for note-taking, learning, and temporary record-keeping. Scholars, merchants, and students frequently used them before committing more permanent records to paper or parchment.

Wooden Writing Tablets (c. 500–700) | @ The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In Platos’ Theaetetus (c. 360 BC), a dialogue between Socrates and the young mathematician Theaetetus on the subject of knowledge, Socrates says:

“For the sake of argument, imagine that our minds contain a wax block […] whenever we want to remember something we’ve seen or heard or conceived on our own, we subject the block to the perception or the idea and stamp the impression onto it, as if we were making marks with signet-rings. We remember and know anything imprinted, as long as the impression remains in the block; but we forget and do not know anything which is erased or cannot be imprinted.” (qtd. in Lees-Jeffries, p. 21)

This metaphor of the mind as a wax tablet was well established in Early Modern thought. Philosophers and educators often likened human memory to a surface that could be inscribed, erased, and rewritten, raising questions about the reliability and permanence of recollection. Hamlet’s statement thus suggests his desire to reprogram his own mind, erasing past distractions in favor of his father’s command for vengeance. However, as the play unfolds, it becomes clear that memory is not so easily controlled; his past thoughts and doubts return, haunting him much like his father’s ghost.

The play-within-the-play

The play-within-the-play, The Mousetrap, is another example of memory’s role in Hamlet. By staging a reenactment of his father’s murder, Hamlet seeks to transform memory into proof, using performance as a tool of revelation. This aligns with Early Modern ideas about theatre itself: plays were not merely entertainment but acts of remembering, where audiences engaged with historical narratives, moral lessons, and political critiques.

In this sense, Shakespeare’s Hamlet is not just a tragedy about an individual’s internal conflict but a profound meditation on the power and fragility of memory. How do we hold onto the past without being consumed by it? How do we ensure that memory serves justice rather than vengeance? And in a world where reality itself is uncertain, how do we know which memories to trust?

Perhaps Hamlet’s greatest tragedy is that, in the end, his memory work leads not to resolution, but to destruction. And yet, the play itself ensures that his story (and his father’s plea to be remembered) continues to echo through time.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is the March/April book in the program Read the Classics in 2025 with Books & Culture. Do you want to join us? Click on the button below for more information:

Lees-Jeffries, Hester. Shakespeare & Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.